The unknown worldview of a popular picture book author

Yoshinaga Koutaku, who has published many best-selling picture books, including the School Series, including "Kyushoku Banchou," was born in Fukuoka Prefecture in 1979. His books are characterized by a style of "Hakata-ben bilingual picture books" that features free-spirited characters drawn with a powerful touch using only paint, a screen composition reminiscent of a film camerawork, and Hakata dialect translations. He has become extremely popular, reading his books to children all over the country and holding over 300 live painting events where he draws with children.

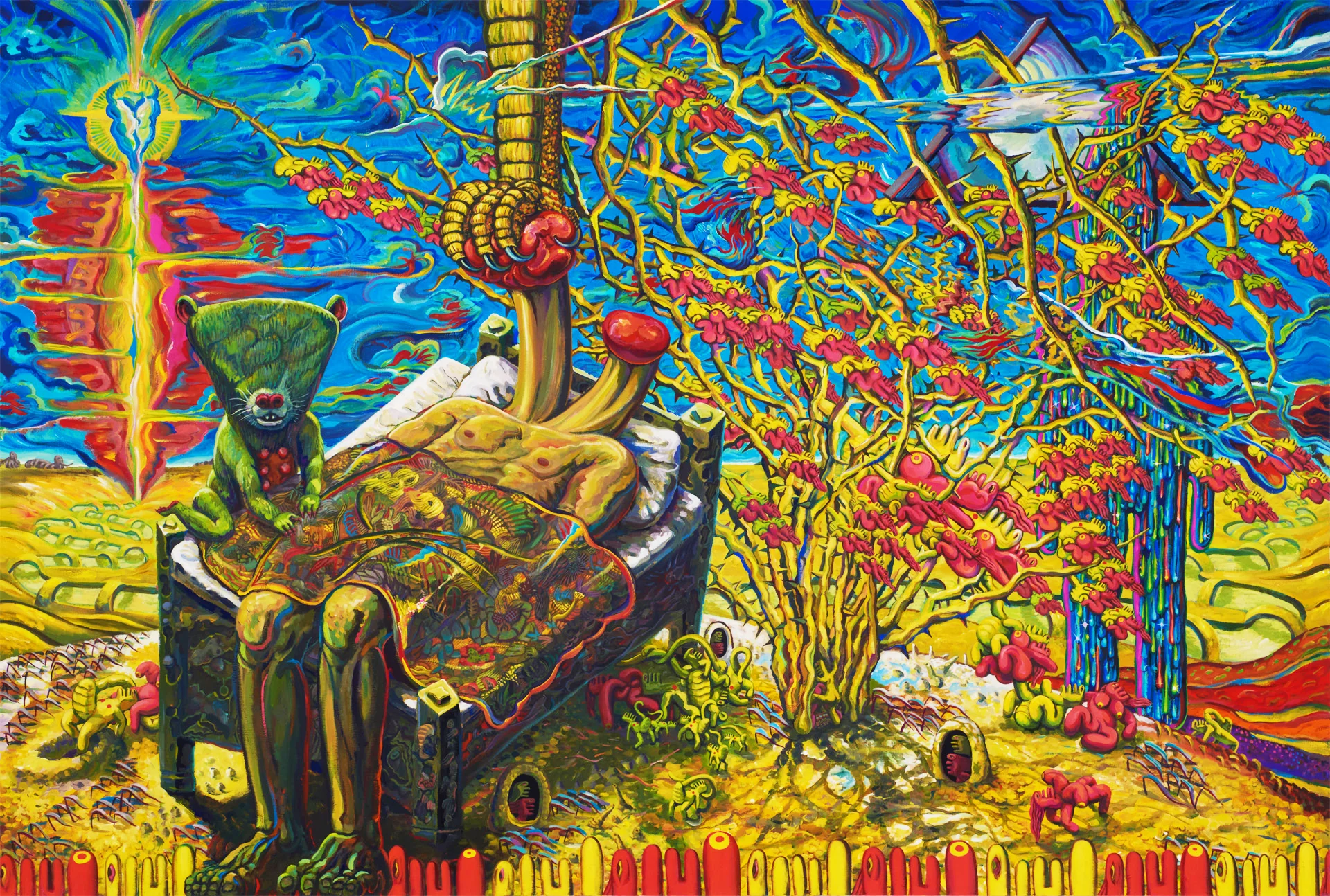

This exhibition, "The Road to This Side of the River Sanzu," will be the first to reveal the unknown worldview of this immensely popular picture book author. The other side refers to the afterlife, a place free from desires and worldly desires. And the other side of the human world, full of suffering. Things that accumulate on the shore of this side of the river, unable to cross it. Yoshinaga approaches the canvas with the image of gazing at them while walking along this side.

Imagining the invisible world

The idea for this theme came from a visit to the areas affected by the torrential rains and flooding in northern Kyushu. The river bore scars that told of the scale of the disaster, but was praised for its divine beauty. What appeared to be driftwood floating there was actually a deer's antler submerged in the river. When I made eye contact with the deer's corpse, life and death were instantly reversed. Staring at the corpse, I realized that what I thought was a rock that had been washed away was actually the deer's head, and that what seemed to be a puddle at my feet was actually a pool of blood. The place that had been glorious and full of life was overturned into the world of the dead, and at that moment the theme of the banks of the Sanzu River emerged. From the world of the dead gazed upon by the living, I had the sensation of the dead staring back at the present world.

Yoshinaga attributes her otherworldly sense to the 100-year-old house she lived in until she was eight years old. "It was common for a weasel to eat up the dinner that was laid out on the table while she was not looking while preparing dinner, or for mice to be lined up in the pest control kits we had in the house. Our house was old and shabby, and at the end of the dimly lit corridor in the spacious house was my grandparents' room and the Buddhist altar, where I was made to recite sutras every morning."

The teachings of her grandmother, who was born into a Jodo Shinshu temple, the feeling of wild animals breaking through the boundaries of the home, and the sense of an invisible world, such as death, existing alongside the space in which we live, seeped into Yoshinaga along with the humidity of the seaside town of Kokura, Fukuoka.

Yoshinaga also traveled around South America from elementary school age with her father, who was involved in research on South American migration. Her father raised funds to build an elementary school there, and she says she still remembers the feeling of a little girl's hand when she shook it with him at a school in the Andes Mountains. The rough hands of people helping with farm work and household chores. She witnessed a life beyond her imagination on the other side of the world she lives in, such as a village lined with shack-like houses.

"When I met the children who were studying art under Sherman when I was in high school, I realized that their art skills were better than anyone in the design department at the school I was attending at the time. Those children told me with shining eyes that they wanted to go to Japan someday, but I thought that this dream might never come true."

After returning to Japan, no one understood me when I told my friends about my experiences, and I felt a sense of resignation as I went through my days as a student, thinking, "Different people are living in different places at the same time, but they never intersect."

The "Daily Sacred Objects Series" that enshrines everyday life

As each day slipped by without anyone to see during the COVID-19 pandemic, the feeling of how irreplaceable those days were came to mind, and so the "Daily Goshintai Series" was born, depicting each day - yesterday, today, and tomorrow - as a sacred object, like a picture diary.

The idea came to me when I traveled to Asian countries after taking a break from being a picture book author in 2017, and noticed how religion is deeply rooted in people's lives, with offerings on the corners of every food stall. I came up with the idea of likening each day to a sacred object, and worshiping 365 sacred objects for 365 days. Instead of pictures that convey the story of my previous picture books, I will now draw sacred objects as symbols of the story of each day, as concrete representations of ideas.

In 2017, at the two-person exhibition "Where Life Lies" at the long-established Fukuoka gallery Art Space Baku, they worked on canvas works for the first time in a long time, and took up the theme of the visible "this world" and the "other world" that transcends human meaning, expressing a worldview that was beyond imagination from their previous picture book works, which became a hot topic. In this exhibition, they have significantly added to those two-dimensional works. In addition to the new Goshintai series, they will also be exhibiting about 30 pieces for the first time, including the short work "Yonagashi Kouta Series" on the theme of the banks of the Sanzu River, reached from an irreplaceable day.

Delivering the joy of living in the present to the next generation

Over the past few years, with his movements restricted and only able to focus on painting, Yoshinaga has lost his father and acquaintances, which also made him keenly aware of the days that were passing. Yoshinaga says that he had always feared death his whole life, but after his father in particular showed him that death comes to everyone, the fear that "had never gone away like a nightmare" disappeared, and he was able to face death with the joy of life.

In the live painting sessions he has done up until now, children have put their brushes in unexpected places, and he says, "It has allowed me to break down my paintings and loosen up my rigid thoughts and brush strokes." Yoshinaga started out as an illustrator in 2002, but his unique style was not accepted anywhere. He spent his days alone and thought he would have to give up on painting, when by chance, the path to picture books opened up for him. He has pursued his career as a picture book author as if pledging his loyalty to the only children who recognized his paintings - those children overlap with the "unreachable" children he met in South America.

Yoshinaga's This Coast will continue to be a picture book, but she believes that if her "pursuit of art, which is the core of her being," remains on the shore of this coast, she will not be able to cross the Sanzu River, so she approaches her paintings as "preparatory work to enrich her own kaleidoscope" and as a celebration of the joy of living each day.

From an early age, Yoshinaga was aware of the randomness of death, and when she encountered the corpse of a deer, she intuitively understood the connection between life and death. In her daily life, which is exposed to anxiety, her "daily prayers" for the joy of living here and now are shown as prayers for the pleasure of the equinox.